Avoiding the premenstrual pseudoscience

Menstrual Mental Health, Online Information, and Responsible Care

Disclaim: This article is not meant in any way to provide medical advice and is not an alternative to medical or psychological treatment. Please do not make hasty health decisions based on an article you read online.

This post is, in a way, a continuation of two previous ones:

One is about how there is no clear distinction between PMDD, severe PMS, and PME;

The other was about recognizing harmful online content, although that post was centered primarily on trauma content in the mental health spheres

Common debates/theories I see in online communities for premenstrual disorders are:

The anti-histamine debate is whether anti-histamines help PMDD symptoms. Some say that if anti-histamines help your symptoms, it means that you do not have “true PMDD” but a different issue

You’re “probably in perimenopause” even if you’re 34 and you need to take HRT.

The estrogen dominance/progesterone deficiency theory, which I will focus on here as an example.

I’ve recently seen women advising other women to take bioidentical progesterone, linking to specific Facebook groups, and quoting a few specific researchers and studies. The line quickly seems to move from “speaking from personal experience as to what worked for me” to making dubious and even dangerous claims (that there is no harm in “just trying” taking progesterone and that if you get negative side effects from taking it, your dose simply isn’t high enough).

Some points to agree on first:

Almost all mental health issues are highly comorbid both with other mental health disorders and with stress and trauma in a bi-directional way. That means that a lot of stress and trauma can lead to the development of a mental health issue, and also, if someone has a mental health issue (that can develop for reasons other than purely stress or trauma), left untreated long enough, that mental health issue will lead to stress, trauma, and other mental health issues.

We don’t have good, clear scientific evidence for many issues. Mainstream medical professionals fail many people who then turn to the internet.

Online, we find a lot of helpful information —and many people selling us things, and it’s hard to know the difference sometimes.

In an era of increasing complexity, our understanding of mental health has become more nuanced and challenging to navigate. We're bombarded with information, diagnoses, and quick-fix solutions that promise to address our struggles, but the reality is far more complicated. Holistic approaches are essential, and we may need to experiment with things that don’t have enough strong supporting evidence yet—but that doesn’t mean we need to stray into pseudo-science or anti-science claims.

I believe in being clear about your scope of practice. I’m not a medical doctor, and I do not have a background in biology. Therefore, I can’t confidently write a post with a tidy conclusion on whether you should try to take anti-histamines or progesterone. That would be unethical, and it’s not my goal in writing this. However, I decided to look into where these recommendations are coming from.

What’s behind the progesterone-deficiency theories?

The conclusion and consensus in PMDD research seemed to be that women with PMDD don’t differ from women without PMDD in hormone levels.12 That suggests that women who experience distressing premenstrual symptoms are reacting to the rise and fall of their hormones, whether their levels are at normal range or not. However, engaging in discussion with the progesterone-deficiency advocates, they claim that these studies can’t be trusted because they only check the hormone levels without looking into the estrogen-progesterone ratio.

There are studies proposing that progesterone has a beneficial role in mood in the female brain and that synthetic progestins cause a negative effect because they suppress ovulation. An important but, though: the review continues to say that there is yet no evidence (in the form of random, controlled trials) that progesterone is beneficial in treating Luteal phase deficiency (unstable progesterone levels in PMDD).

I did find a case study3 of a woman who was treated with bioidentical progesterone, maca, magnesium, and B vitamins who had improvements in the psychiatric symptoms of PMDD (along with premenstrual headaches, cramps, and menstrual flow) within three months of starting the protocol.

I also found a book, The Miracle of Bio-Identical Hormones: How I Lost My Fatigue, Hot Flashes, ADHD, ADD, Fibromyalgia, PMS, Osteoporosis, Weight, Sexual Dysfunction, Anger, Migraines... and More By Michael E. Platt. Before noticing that a man wrote the book and yet claims that the author cured hot flashes, I started reading the sample chapter, which starts out explaining that bioidentical progesterone is usually made from soy or yam. I found that interesting because soy is a common food intolerance in people with ADHD, and it also contains phytoestrogens. Then I looked closer at the book and thought that was a strange title for a book written by a man (and it also sounds like a lot of things to claim). I clicked because, hey, maybe he’s trans. I saw he had another book called Miracle of Bio-Identical Hormones and another called Estrogen Dominance.

Reading further in his book, he seems to claim a lot is caused by hormonal imbalance, including ADHD (a claim I’d never seen before), cancer (?), and menopause (something that all human females naturally go through).

Interestingly, he says that doctors don’t recommend or use hormones because drug companies don’t recommend them—despite writing several times in the introduction that bio-identical hormones are made by Upjohn and Pfizer, themselves drug companies.

I couldn’t find much about Michael E. Platt online, except that he has a website with a shop that sells pages of products, including “bundles” of his book with meal plans and progesterone creams. He also states in his book that all his advice is based on his clinical observations and not any studies or other sources. I wonder why he would not try to get studies done on this theory if he believed in it so much.

He also makes grand claims that would be better served with some citations and explanations…

I found it strange that he’s saying that estrogen causes heart attacks because I remembered reading

“Observing that women tended to have lower rates of heart disease until their oestrogen levels dropped after menopause, researchers conducted the first trial to look at whether supplementation with the hormone was an effective preventive treatment. The study enrolled 8,341 men and no women"

In general, it seems weird to make it seem like we have a “good” and “bad” hormone when both estrogen and progesterone are important to our hormonal cycle.

At least he acknowledges that “bio-identical” does not always = “safe.”

The Internet as a Double-Edged Sword

The internet has become a critical resource for those who were failed by traditional medical systems. It offers invaluable information and community, but it's also a marketplace where everyone seems to be selling something. How do we distinguish between genuine help and opportunistic marketing?

Red Flags in Online Health Information

Be wary of sources that:

Claim to have the "secret" information that all doctors are hiding

Offer universal solutions without personalized assessment

Push products with vague promises of healing

Suggest simply increasing dosages without professional guidance

Evaluating health claims

Check the source:

Is the information from a peer-reviewed journal?

Are the authors credentialed experts?

Does the source have potential financial conflicts of interest? In our example, it matters whether the website sells progesterone products if you’re trying to find information on progesterone.

Look for scientific consensus:

Are multiple independent studies showing similar results?

What do major medical associations say about this claim?

Are the conclusions based on robust research or anecdotal evidence?

Be wary of:

Absolute statements (e.g., "This ALWAYS works")

Claims of miraculous, universal solutions

Information that sounds too good to be true

For example, if you take a quiz on one of these websites and you happen to get the result that you have low progesterone… Maybe everybody or almost everybody taking that quiz will get the same result?

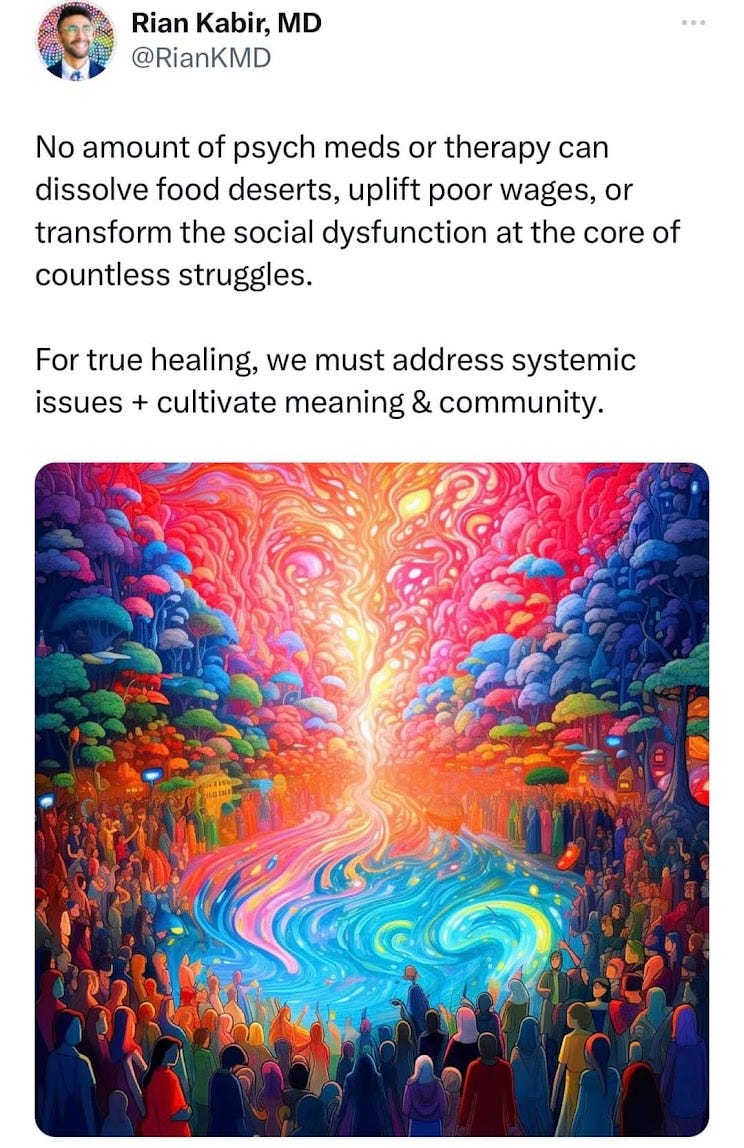

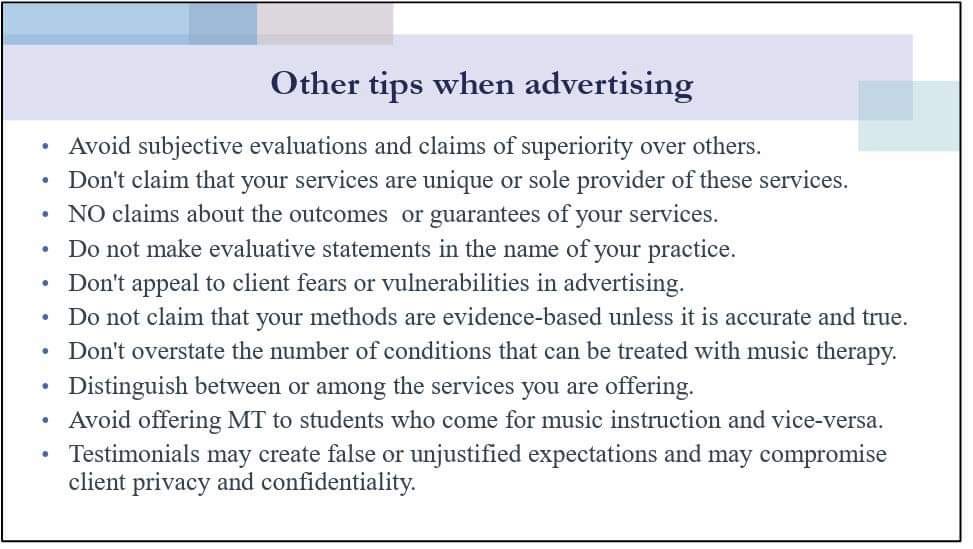

Credentials, licensing, and ethics

Licensed professionals such as medical doctors are bound by a code of ethics. If they prescribe something that harms a patient, the patient can sue, or there can be an investigation, and the practitioner could lose their license.

As a therapist (in training), I can't promise a client that I will heal their depression or that they’ll feel better in 15 sessions. There are many things that I can help with, many things that I think I would be good at as a therapist. But I also know there are other issues I don't have as much experience in and haven't read as much about. I may have to tell a client that if they want somebody who is specialized in working with contamination OCD, that's not me. I can still see them as clients, try to help, and do some research. But I won't be an expert in contamination OCD in one day. I'm ethically bound to tell people what I can and can't deliver. I can say I think I may be a good fit, or I think we may not be a good fit. Let's see, and you can see how you feel as well.

The temptation of promised solutions

Despite challenging the claims of the progesterone-deficiency proponents, I have to admit that throughout the conversation and research, a part of me asked, “What if they’re right? What if I just take progesterone, and it solves all my problems?”

I happen to be in a pretty good place with my mental health. I enjoy my life, have been dealing well with my symptoms (which are a lot more manageable than they used to be), and I have a therapist I know I can lean on if things get tough again.

But I can imagine how it must be to be in a crisis point, experiencing severe symptoms every month, and come across a solution that seems perfect if you “just” pay for this product. These companies blindly sell products without responsibility and are not bound by ethical codes or licensing boards. When the person buys their product, it may have negative side effects. That's dangerous. That worries me.

Diagnosis: A Tool, Not a Definition

Diagnoses can be helpful when they provide tools and understanding. However, they become problematic when they:

Pathologize normal human experiences

Become a way to explain away systemic challenges

Make us feel fundamentally "broken"

What a diagnosis should do:

Provide a framework for understanding symptoms

Guide potential treatment approaches

Offer validation of experiences

What a diagnosis should not do:

Reduce a person to a set of symptoms

Suggest a one-size-fits-all solution

Create a sense of permanent limitation

If you’re struggling with anxiety, how do you decide what the anxiety is caused by? It's not easy. If you take pills, it's not supposed to matter if your anxiety is caused by PMS, a test, a bad relationship, childhood trauma, etc. But it obviously matters. Of course you’ll be stressed if you’re in a long-term relationship with an unsupportive or abusive partner, if you’re constantly working but unable to make ends meet, if you can’t keep a job for longer than a year because every few months you have a breakdown.

On the other hand, untreated conditions, like ADHD or premenstrual symptoms, can disrupt life. Even if you start with "pure" PMDD, left untreated, you start missing work or fighting with your partner, and then that stress spreads to the whole month because you feel like you need to "catch up" in your follicular phase.

Societal Context Matters

Many struggles we experience—like social anxiety or difficulty maintaining a household—are often symptoms of broader societal issues. Our current system demands constant productivity, isolates us, and creates inherently challenging environments. Algorithms tailor content to keep our attention, offering possible explanations and solutions to issues we’re struggling with.

Experiencing social anxiety (for example) isn’t necessarily a sign that something is wrong with you, whether it’s autism or a hormonal imbalance. Sometimes, social anxiety is a normal response to an increasingly individualistic and isolated world, where social interactions become draining instead of nourishing. Similarly, if you’re feeling exhausted before your period, it may not be a sign that something is wrong with your body - it may be requesting that you rest because you have different physical needs during your luteal phase compared to your follicular phase when your body is gearing up for ovulation and possible conception.

Closing Thoughts

The path to mental wellness is not about finding a single solution or collecting diagnoses. It's about:

Understanding the complexity of our experiences

Seeking responsible, ethical care

Recognizing that our challenges are often interconnected with broader societal contexts

Being critical consumers of health information

A Life Less Miserable is a free publication that I work on in my spare time (that is, when I should be working on my thesis or tackling my to-do list). It will remain free and without affiliate marketing or selling courses or products, always. However, tips are appreciated if you enjoy/are helped by my content and have the resources available.

Additional resources

Sundström-Poromaa, I., Comasco, E., Sumner, R., & Luders, E. (2020). Progesterone – Friend or foe? Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 59(100856), 100856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2020.100856

Cary, E., & Simpson, P. (2024). Premenstrual disorders and PMDD- a review. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 38(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2023.101858

An Integrative Approach for Improving and Managing Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD): A Case Report. (2023). Current Research in Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2201.100211